Exploring Beit Shean: A Visitor's Guide

If you want to relive the glory days of ancient Rome, this well-preserved archaeological site in Israel is one of the best tourist attractions in the country to visit. Much of the Roman city has managed to survive, with the colonnaded streets and temple remnants offering you the chance to have a peek into the lifestyle here under Roman rule. The setting, in a valley surrounded by gorgeous mountain scenery, is extremely dramatic, adding to the heady atmosphere of past grandeur.

Roman Theater

Start your sightseeing tour at the Roman Theater. Built during the reign of Septimius Severus, during the late 2nd century, Beit Shean's Roman Theater is the best preserved in Israel. It had seating for 6,000 spectators, with the lower part of the structure built into the ground and holding semicircular tiers of seating. The upper part is born on massive substructures, with nine entrances leading to the horizontal gangway halfway up the auditorium. The upper seating tiers have been partly destroyed, but the lower seating rows are excellently preserved. There are also substantial remains of the stage wall, which was originally richly decorated with columns and statues.

Tell el-Husn

Immediately north of the Roman Theater, you'll find Tell el-Husn, the archaeological site's major point of interest. Excavation work on this settlement mound during the 1920s brought to light stele and sculpture dating from the period of Egyptian rule. Much of what was unearthed (including a stele of Pharaoh Sethos I and a stele depicting the war goddess Anat) can now be seen in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. Further excavations since 1986 have yielded such impressive results that Beit Shean now ranks as one of the most important archaeological sites in Israel. If your visit is short on time, due to the vast amount of ruins in this area, Tell el-Husn should be at the top of your things to do list while at the site.

Since Beit Shean was destroyed by an earthquake shortly after the Arab conquest, the building materials of the ancient town were not - as was the case for example in Caesarea - reused in later buildings. This simplified the work for archaeologists, who only had to re-erect walls and structures that had collapsed in the earthquake.

In the south part of the site, another excellently preserved Roman and Byzantine theater, also seating 6,000 spectators, has been brought to light. North of this is a bath house from the Byzantine period centered on an inner courtyard with colonnades around three sides and preserving remains of the original mosaic and marble decoration. A fine Tyche mosaic (6th century AD) was found in a Byzantine building immediately northeast of the baths; it depicts Tyche, goddess of fate and good fortune, with the cornucopia, which was one of her attributes.

From the bath house, steps lead up to a colonnaded street linking the theater and the baths with the center of the city. At its north end is a broad flight of steps leading up the remains of a Roman temple of Dionysus. To the east of this temple are foundations and architectural fragments belonging to a nymphaeum and a basilica that served in Roman times as a meeting place and marketplace. Southeast of the basilica, a row of monolithic Roman columns and part of a Byzantine street of shops lead to the southern part of the town.

Byzantine Remains

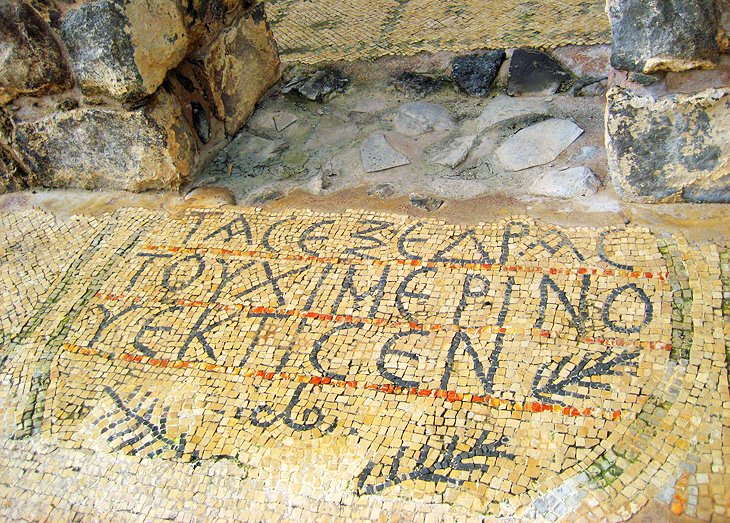

Byzantine remains were found to the north of Tell el-Husn, on the far side of the Harod valley. Here, in AD 567, a noble lady named Mary and her son Maximus founded a monastery, with fine mosaics that are now under a protective roof. The entrance leads into a large trapezoidal courtyard, with a mosaic pavement depicting animals and birds, two Greek inscriptions, and in the center - within a circle of 12 figures representing the months - the sun god Helios and the moon goddess Selene. To the left is a rectangular room with a mosaic, which an inscription records "was completed in the time of Abbot George and his deputy Komitas." Other mosaics (vine tendrils, hunters, animals) are in a small room opposite the entrance, as well as in the eastern part of the monastery, the narthex of the church, and in the church itself. In the sanctuary are gravestones inscribed in Greek.

Seraglio

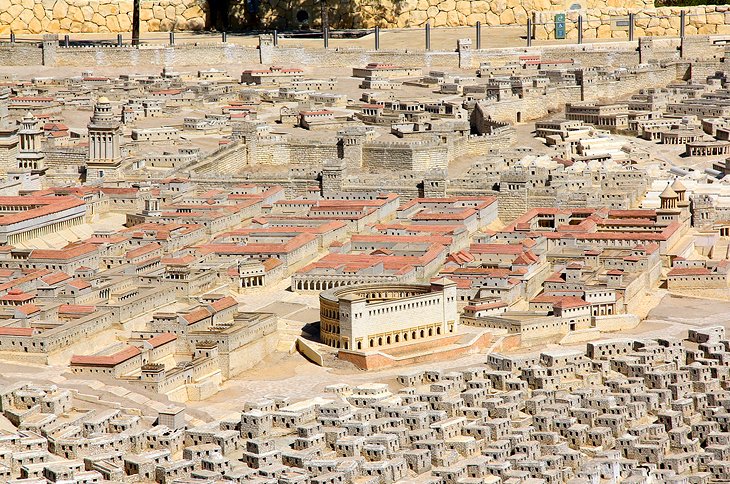

The Seraglio (the former Ottoman government building) is on the east side of Beit Shean and acts as a visitor center for the archaeological site. Note the antique columns framing the doorway to the building. From here, King Saul Street bears right, passing an area where remains of a Roman hippodrome were found, and comes to a road on the right, which runs down to the Roman theater. Inside the building itself is some useful information about the history of the site, and just outside is a good scale model of what Beit Shean would have looked like during the Roman era.

Tips and Tactics: How to Make the Most of Your Visit to Beit Shean

- Bring a sun hat and plenty of water - especially in summer. It is extremely hot at the site and there is little shade.

- From Jerusalem, bus 961 has several departures daily to Tiberias, which passes by Beit Shean. The journey takes two hours.

- From Tiberias, you can also take bus 961, which drops off passengers at Beit Shean on its way to Jerusalem. The journey takes one hour.

History

American archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania carried out excavations here in 1921-23 and identified 18 occupation levels, the earliest dating back to the 4th millennium BC. Beit Shean first appears in the records in Egyptian documents of the 19th century BC. After his conquest of Canaan in the 15th century BC, Pharaoh Tuthmosis III fortified the town. In the 11th century, it was captured by the Philistines advancing inland from the sea.

David conquered the Philistine town, which for some unknown reason was abandoned in the 8th century BC. In the 3rd century BC, it was resettled by Scythian veterans and renamed Scythopolis. In the Hasmonean period (2nd and 1st century BC) numbers of Jews came to live in the town. In 63 BC, Pompey declared it a free city, and it became a member of the Decapolis, the League of Ten Cities. Under Roman rule, thanks to its productive agriculture and textile industry, it enjoyed a fresh period of prosperity, to which the numerous remains bear witness.

In Byzantine times, the town had a population of some 40,000; most of them were Christians, but there was also a Jewish community. This period came to an end with the Arab conquest in 639, and soon afterwards the town was destroyed by an earthquake and abandoned.

In the 12th century, Beit Shean was held by Tancred, Prince of Galilee. After its conquest by Saladin in 1183, the town had a Jewish population, one member of which was Rabbi Estori Haparhi, who wrote the earliest work in Hebrew on the geography of Palestine. Later, increasing numbers of Arabs settled in the town, and its name was changed to Beisan. A relic of the Turkish period is the Seraglio in the municipal park, an administrative building erected in 1905.